Every bit as quietly charismatic as you’d expect, Mark has a lovely laid-back manner that puts the riders instantly at ease. Yet there’s also a stern side, which emerges when he clearly feels a rider isn’t listening, with exercises often repeated until performed to his satisfaction. And his advice works its magic: horses who start out rushing and on the forehand finish the session in a far better balance, while riders who have the handbrake too firmly on are encouraged to ride in a more flowing rhythm that’s much nicer to watch.

At the outset, Mark explains that the focus of the morning is going to be playing around with different lines and distances to make the horses more obedient and supple. When working on the flat, he wants the horse to go forward from the leg, slow down and be obedient to the hand, and to be in self-carriage.

“Our job as a rider is to help the horse. We have to make them bend through the body and stay in a balance and rhythm, as horses won’t do this naturally on their own,” he explains. “It’s like driving a car – you’ve always got to make little adjustments and think what’s happening underneath you. Is the horse listening to your leg? Is he being obedient to your hand? Will he shorten or lengthen? If not, you’ve got to do something about it.

“So if they are not listening to your leg, you’ve got to give them a boot, or a nudge with the spur or even a slap with the stick, and if they’re not listening to your hand you’ve got to give them a good half-halt and say ‘Oi, I mean it, you listen.’ And it doesn’t have to be done in a rough way, and you don’t get angry about it; you just have to be firm and very consistent in what you ask. It’s no good doing one thing one day and then something different the next, because that just makes the horse confused.”

Mark gets the riders to trot around a little bit, so he can take a look. He tells them to do plenty of transitions, changes of rein, changes of tempo and lateral work in their warming up, to loosen the horses and start to make them obedient. “Make sure you’re always asking something of them, so you know that when you come to the jumping you have all your aids in place and the horse is actually listening to you.”

When Lily attempts to ride forward and then slow down again in the trot, her horse argues. “Do that again and repeat it until he listens and comes back without arguing. And don’t forget to always reward the horse with a simple pat on the neck if he does something correct,” advises Mark.

Mark tells the riders to go up into the canter and start changing the tempo, riding forward for a few strides before collecting again, to make the horse supple longitudinally. He then gets them to ride some canter leg-yield, pushing the horse away from the inside leg. This can be ridden both ways; when on the right lead, the horse can leg-yield to the left or in counter-canter to the right. “It’s about keeping the horse balanced, straight, between your legs and riding them into both reins.”

Amy’s big, green youngster is initially a little confused by the leg-yielding and changes leads, but Mark tells her not to worry. “Just bring him back and correct him. He’s got to learn to accept the leg without changing.

“Leg-yield is an important training exercise for all levels, as it makes the horses more supple and gets them accepting the leg and the rein. Some of your horses start arguing as soon as you put your leg on and that’s just about them understanding what you’re asking.

“To be able to move the horse one way or the other is very useful: if you’re jumping and you want to create more distance, you just use your inside leg to move them sideways and give yourself a bit more space.”

Teaching flying changes

Mark’s first exercise is one he uses a lot at home and it’s good for teaching the horse about changing leads. Most of the horses in this group are young and don’t do flying changes yet, but Mark says that doesn’t matter. “The earlier you teach them about changing leads, the better, and this is a simple way of getting the idea in their head.”

Mark has set out four tiny jumps down the middle of the arena for the riders to make a serpentine over, asking for a flying change over each rail.

On approach to the fence, the rider should keep the horse straight and collected; if there is the option of going off a long stride or waiting, waiting is definitely the preferred option here. As the horse is about to take off, the rider uses a little bit of outside leg, opens the inside rein and turns their body in the new direction to ask for the change. Don’t look down to see if the horse has changed, warns Mark. If the horse doesn’t change or gets a bit long, simply half-halt, correct and re-balance before continuing on through the exercise.

“The changes are really just teaching the horse about being balanced,” says Mark. “It’s a little trick and once they learn it, it’s very easy for them, so don’t panic if they don’t get it straight away.”

Amy is trailblazer for this exercise and positions her horse beautifully over each fence, getting a perfect change every time. Mark praises her, but notes that her horse gets a bit ‘gobby’ when she asks him to pull up at the end. “Afterwards I would have cantered around and gone forward and back and then forward and back again, just to re-establish that he has to wait for you,” he says.

Lily doesn’t use as much of an opening inside rein as Mark would like to see, although her horse does get most of the changes. Mark tells her not to fix her hand too much. “Don’t rest on your hands. Take your weight in your heel so you can support yourself with your lower leg.”

Meanwhile, Amanda’s mare is a little bit long and in too much of a rush, so Mark gets her to repeat the exercise and slow the whole thing down. “Don’t go off a long stride. Make her wait,” he says. “These are tiny jumps – don’t ride them like a 1.50m wall. It’s all about keeping the canter rhythm and the jumps just come in the way. When the fences are low like this, it’s good to make the horse wait. Even if they make a mistake, they are not going to frighten themselves.”

A question of control

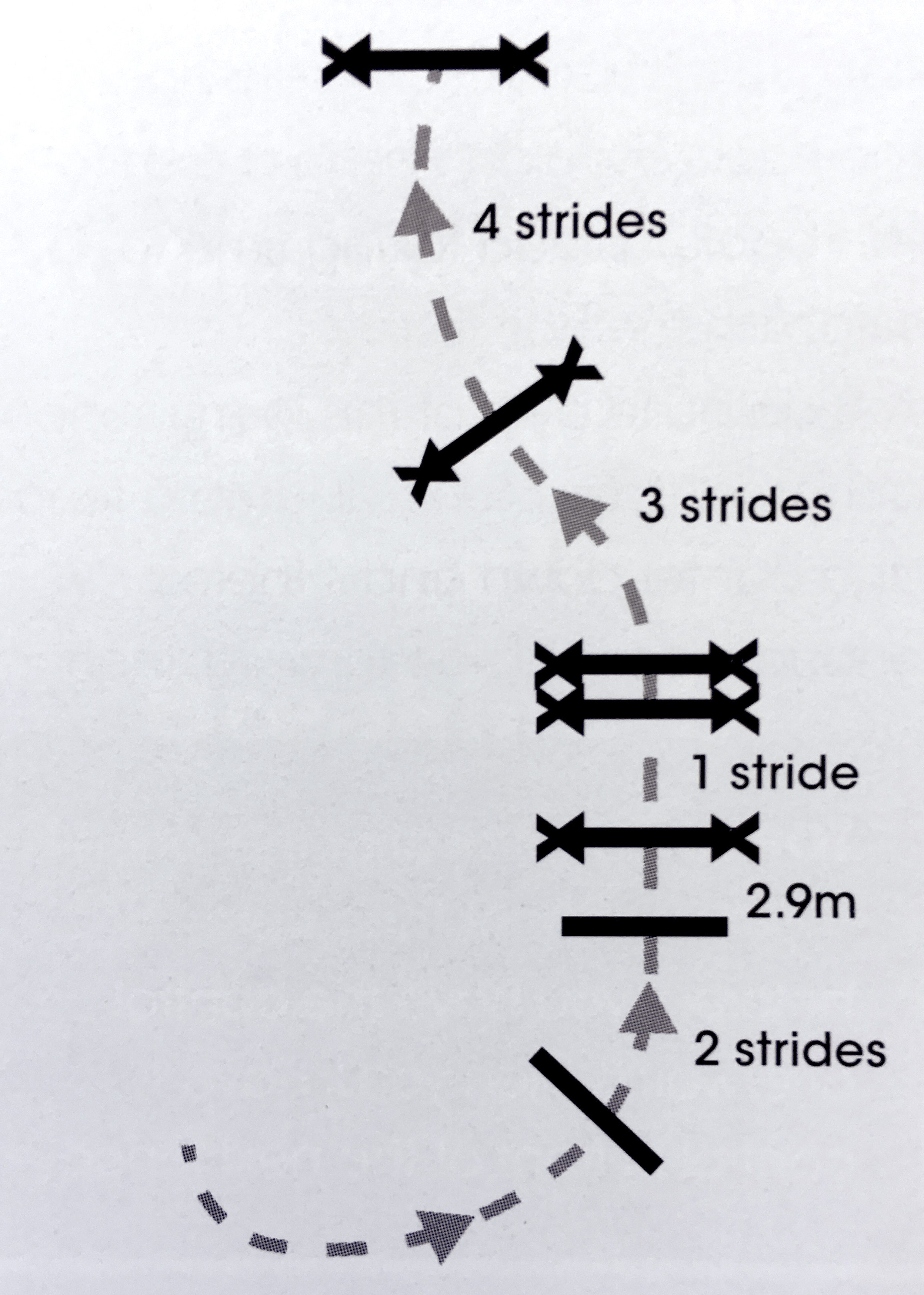

The next exercise of bending lines consists of cantering over a ground pole on a curve to a one-stride double (vertical to oxer), with a groundline set at just under 3m. The riders then land and turn left, cantering three strides to another pole on the ground. Over the pole, they ask for a flying change to the right and canter four strides down to a vertical (see diagram below).

Mark warns the riders to control the horse’s shoulders through the left turn, so they don’t drift out to the right. They then have three strides to make the horse straight before asking for the change to the right. “You’ve got to be quite quick to turn, balance, straighten and change. If you’re just hanging on, they probably won’t change.”

All the riders complete this exercise nicely, although Mark warns Fran not too use too much hand on the rather keen Leo, as she gets four strides and five strides, rather than the required three and four. “Even if he’s a little bit strong, don’t be too strong back. You’ve still got to let him keep his rhythm and canter.”

Next, Mark adds a related line on to the exercise, consisting of an oxer, seven strides to a vertical. At the end of the line, he wants the riders to turn a circle and bring the horse back under control. “Always finish with the horse in a nice balance and rhythm. Never just pull up and stop,” he says.

Amy’s long-striding Rock It cruises down the line in six strides, rather than the normal seven, so Mark tells her to go again. “Use your upper body a little bit more – you’re too forward with your body. Keep a little bit of a connection with your hand.”

At the end of the exercise, Mark gets them to ride some canter-walk transitions to make the horses more obedient, even Amanda with her very green mare. “Obviously she’s not going to be able to do it like the three-star horse, so you can allow her to do a few steps of trot; you’ve got to take into account the level the horse is at. But don’t treat her like a baby – she’s got to learn balance, so we’ve got to challenge her a little bit,” he explains. “You can never do too many of these transitions.”

Land and wait

In order to teach the horse to wait in balance after the fence, Mark gets the riders to go down a line and halt at the end in a straight line. The exercise is approached on a curve over a ground pole, either off the left or right rein, before jumping the one-stride double and cantering four strides down to another one-stride combination, oxer to vertical. They then canter away on landing, sit up and shorten, before halting at the arena fence and asking for a few steps of rein-back (see diagram two below).

The riders shouldn’t be in a rush to rein-back, instead taking time to establish the halt before stepping back.

“I do quite a lot of this in my school at home,” says Mark. “I’ll jump a fence and canter down and if there’s enough room I’ll ride forward, then shorten and collect, collect, collect and let the wall at the end help the horse stop. Using the wall to reinforce the halt makes the horse sit and stop with the hind leg underneath.

“This exercise teaches the horse to wait in balance, so all we have to do after the fence is sit up and the horse balances himself. Then you have a nice balance to ride through the turn, instead of saying slow down, slow down, all the way.”

Style file

Lily and Lam

Mark notes the first thing Lily does when she lands is grab the rein. “That’s typical of someone who rides a horse that is a little bit strong. Their first reaction is ‘I’m being run away with; I’ve got to hold on.’ But we’ve been doing a lot of short exercises, so Lily’s horse is not thinking about running and she’s actually ending up having to chase him down the line, which is what makes him quick. She needs to land and be ready to feel whether he is waiting or running away, rather than automatically slowing down. She has to get out of this habit of landing and holding. It’s just about keeping that rhythm.”

Amanda and Lola

Mark says Amanda’s horse is still green and not very well-balanced yet. “She’s built a little bit on her forehand, which is why she struggles when she gets long. The more Amanda can keep her together and the more she can do those transitions forward and back and from canter to walk, the more she’ll start to find her own balance.”

Amy and Rock It

Amy’s horse has a big stride and when he gets long and strung out he doesn’t use himself, notes Mark. “Amy has to do lots of transitions on the flat, forward and back, to get him to react a bit more quickly in those downwards transitions. Half-halt and then relax again, because the half-halt has to mean something. She needs to sit up more with her upper body in the air, so that when he lands he is more balanced. I don’t want her to hold him off the front rail and protect him – he has to learn to back himself up at the fence.”

Fran and Leo

Because Leo is a bit strong, Fran is riding on her hand a bit too much, says Mark. “I don’t want Fran to think backwards because then she doesn’t get the distance; she should allow her horse to travel forward with her leg on. When she’s schooling at home, she has to do a lot of transitions in the canter, so that she is confident that when she rides forward, he will come back again.”

Mark’s conclusions

You have to think about what’s going wrong in your show jumping rounds. Do you have control? If you don’t have control, go back to your flatwork. Work over poles on the ground, riding forward and then slowing down. If you use poles or very low fences, then the horse is not going to get a fright when they get tangled up in it, but they learn. Don’t leave it until you’re jumping 1.20m to suddenly decide you haven’t got any control.

Practice your flying changes over a pole on a ground, so that you are confident you can come in and ask for a change and stay balanced. It doesn’t matter if you don’t get the change, but if you don’t ask, you’ll never get it, except when the horse decides to do it himself – we want to be in charge. You’ve got to get into the habit of asking.

- This article was first published in the January 2017 issue of NZ Horse & Pony